When working with geometry, you'll need to do some intersection tests at some point. Sometimes it's directly related to graphics, but sometimes it helps determine other useful things, like optimum paths. This article is meant to give the up-and-coming game developer a few more tools in their computational toolbox.

For this article, I'm assuming you know all about vectors, points, dot and cross products. We'll cover some quick properties of polynomials, some things about some basic curves, and then go over intersection tests.

The Stone-Weierstrass theorem states that any continuous function defined on a closed interval can be uniformly approximated as closely as desired with a polynomial function. For graphics and game development, that means that most 2D objects we deal with can be expressed as polynomials. The key to these intersection test methods is using that to our advantage.

In order to find all our intersection points, we need to know how many intersections there can be between 2 polynomials. Bezout's theorem states that for a planar algebraic curve of degree n and a second planar algebraic curve m, they intersect in exactly mn points if we properly count complex intersections, intersections at infinity, and possible multiple intersections. If they intersect in more than that number, then they intersect at infinitely many points, which means that they are the same curve.

Bezout's theorem also extends to surfaces. A surface of degree m intersects a surface of degree n in a curve of degree mn. As well, a space curve of degree m intersects a surface of degree n in mn points.

The key here is to identify how to count intersections. For example, if 2 curves are tangent, they intersect twice. If they have the same curvature, then they intersect 3 times. Simple intersections (not tangent and not self-intersecting) are counted once. So how do we count intersections at infinity? Using homogeneous coordinates, of course!

Counting intersections at infinity sounds hard, but we can use homogeneous coordinates to do this. Here, we define a point in 3D homogeneous space \((X,Y,W)\) to correspond to a 2D point \((x,y)\) whose coordinates are \((X/W,Y/W)\). This means a 3D homogeneous point \((4,2,2)\) corresponds to a the 2D point \((4/2,2/2) = (2,1)\). Going the other way, the 2D point \((3,1)\) becomes the 3D point \((3,1,1)\), since the transformation back to 2D is simply \((3/1,1/1) = (3,1)\). This creates some weird equalities, but you can visualize this 3D-2D transformation as projecting the points (and curves) in 3D onto the plane \(z=1\).

This helps us with define infinities with finite numbers. Let's say we have the point \((2,3,1)\) in homogeneous coordinates. If we changed the weight coordinate W so that we had \((2,3,0.5)\), the 2D point would be \((4,6)\). Smaller weights mean larger projected coordinates. As the weight approaches zero, the 2D point gets larger and larger, until at W = 0, the projected point is at infinity. Thus, any homogeneous point \((X,Y,0)\) is a point at infinity.

Aside: Equations in Homogeneous Form

Usually, polynomials have terms that differ in their algebraic degrees. Some are quadratic, some cubic, some constant, etc. The polynomial takes the following form:

\[f(x,y) = \sum_{i+j\le n} a_{ij}x^iy^j = 0 \]

However, the same curve can be expressed in homogeneous form by adding a homogenizing variable w:

\[f(X,Y,W) = \sum_{i+j+k = n} a_{ij}X^iY^jW^k = 0 \]

Here, every term in the polynomial is of degree n.

To use polynomials effectively, we need to be familiar with how they can be expressed. There are basically 3 types of equations that can be used to describe planar curves: parametric, implicit, and explicit. If you've only had high-school math, you've probably dealt with explicit curves a lot and not so much with the others.

Parametric: The curve is specified by a real number \(t\) and each coordinate is given by a function of \(t\), like \(x = x(t)\) and \(y = y(t)\). Rational polynomials are defined the same way, but each coordinate divided by a different function of \(t\), like \(x = x(t) / w(t)\) and \(y = y(t)/w(t)\).

Implicit: This curve takes the form \(f(x,y) = 0\), where the point \((x,y)\) is on the curve.

Explicit: This is really a special case of both parametric and implicit forms. The explicit form of a curve is the classic \(y=f(x)\) form.

Let's start with a very basic curve: the line. It's a degree-1 polynomial. There are many definitions of this kind of curve. Some are helpful for games and others...not so much. Some you may have seen in algebra class and others you may be seeing for the first time.

Common Forms

Slope-intercept: \( y = mx+b \)

Point-slope: \( y - y_0 = m(x-x_0) \)

Affine: \( P(t) = [(t_1-t)P_0+(t-t_0)P_1] / (t_1-t_0) \)

Vector Implicit: \((P-P_0)\cdot n = 0\)

Parametric: \( P(x(t),y(t)) = (x_0+at,y_0+bt) \)

Algebraic Implicit: \( ax+by+c=0 \)

In secondary schools, they use the first 2 methods almost exclusively, but these turn out to be the least helpful for computing. Here, I've tried to order the definitions from least helpful to most helpful for our needs.

Probably one of the most useful forms, the implicit form is nice for a few reasons. First, we can express it in homogeneous coordinates: \(aX+bY+cW=0\). From here, we can define the coordinates as an ordered triple \((a,b,c)\) and then modify the equation to use the dot product so we can use a simple test if a point lies on a given line in implicit form:

\[L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) = 0\]

Signed Distance From a Line

Although this isn't strictly an intersection test, this method is valuable enough to mention here. Although points that lie on a line satisfy the equation \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) = 0\), if the point is not on the line, the scalar value can let us know on which side of the line the point lies by the sign. If \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) > 0\), the point lies on one side of the line; if \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) < 0\) it lies on the other. This is a convenient way of dividing a plane into 2 separate regions.

This scalar value is also a scaled distance from the line. If only the relative position of a point from the closest point on a line is desired, then this scalar can suffice. However, if true distance is required, then the full signed distance formula for a point \((x,y)\) from an implicit line defined by the ordered triple \((a,b,c)\) is given by the following:

\[D = \frac{ax+by+c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}\]

Implicit Line from 2 Points

This ordered triple form a convenient way to define coordinate axes. For example, the x-axis can be defined as \((0,1,0)\) and the y-axis can be defined as \((1,0,0)\). The ordered triple is also really nice because we can compute it really easily if we have 2 points. Let's go back to our vector math to see how this might work.

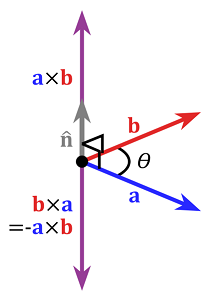

In the above picture, two vectors \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are crossed to produce a 3rd vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a}\times\vec{b}\). This vector \(\vec{c}\) is orthogonal to the vectors \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\), meaning that \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). This is important for this next neat trick.

Imagine we have points \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). To tie back into the example above, let's let \(\vec{a} = P_1 = (x_1,y_1,w_1)\) and \(\vec{b} = P_2 = (x_2,y_2,w_2)\). If we cross these vectors, we get a vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a} \times\vec{b}\) for which \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). Since \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are points, we could say that \(\vec{c} = (a,b,c)\), an implicit ordered triple that passes through both points. We can check that the line given by \((a,b,c)\) passes through both points by the dot product method.

\[L(a,b,c) = P(X_1,Y_1,W_1) \times P(X_2,Y_2,W_2)\]

Line-Line Intersection

Using the same kind of logic, we can get the point at which 2 lines intersect. To use the cross product example again, let's let the vectors be the ordered triples of 2 implicit lines, \(\vec{a} = (a_1,b_1,c_1)\) and \(\vec{b} = (a_2,b_2,c_2)\). Again, crossing these vectors yields a vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a} \times\vec{b}\) for which \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). Since \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are lines, we could say that \(\vec{c} = (X,Y,W)\), the intersection point of both lines. This point has to be on both lines, and we can verify that using the dot-product method.

\[P(X,Y,W) = L(a_1,b_1,c_1) \times L(a_2,b_2,c_2)\]

Connection to Bezout's Theorem

Lines are degree-1 algebraic curves. Bezout's theorem states that 2 lines must intersect at exactly 1 point. So what happens with parallel lines? Well, if we use homogeneous coordinates, the intersection point will take the form \((X,Y,0)\), a point at infinity. Bezout's theorem still holds for that case.

Sometimes it's advantageous to define some curves as parametric and some as implicit to solve for intersections. Most times, it's better to define the simpler curve as parametric and the more complex curve as implicit is possible. This method solves for all algebraic intersections, which may or may not be "real" intersections. As well, multiple roots might come up, in which case we have to reconcile this with our intersection counting methods above.

Let's take a fairly common case: line-circle intersection. Bezout's theorem says we will get 2 intersections since a circle is a degree-2 algebraic curve. The parametric line at point \((x_0,y_0)\) with direction \((c,d)\) and implicit circle centered at \((a,b)\) with radius \(r\) are defined as follows:

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,y) &= (x-a)^2+(y-b)^2-r^2 = 0 \\

L(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= x_0+ct \\ y&=y_0+dt \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

We can substitute the parametric equations into the implicit equation to get a polynomial in terms of the parameter \(t\). The roots of the polynomial are the parameter values at which the line intersects the circle. Substituting, we get:

\[

\begin{aligned}

0 &= (x_0+ct-a)^2+(y_0+dt-b)^2-r^2 \\

&= [c^2t^2+2c(x_0-a)t+(x_0-a)^2]+[d^2t^2+2d(y_0-b)t+(y_0-b)^2]-r^2 \\

&= (c^2+d^2)t^2+2[c(x_0-a)+d(y_0-b)]t + [(x_0-a)^2+(y_0-b)^2-r^2] \\

&= At^2+Bt+C \\

\end{aligned}

\]

This looks promising. The quadratic formula can solve really quickly for the roots of the polynomial:

\[t=\frac{-B\pm\sqrt{B^2-4AC}}{2A}\]

The result of this will either be 2 complex roots, 1 real root, or 2 real roots, depending on the discriminant \(B^2-4AC\). The 1 real root case means the line is tangent to the circle, which according to our intersection counting rules above, we count twice. Bezout's theorem still holds. (Note: technically we have 1 real root with multiplicity 2 since we have the roots \(t = (-B+0)/2A\) and \(t = (-B-0)/2A\).)

That might be nice mathematically, but what does that mean for us? Well, the parameter \(t\) has to be a real number, so the real roots are values of \(t\) that the line intersects, so plugging the roots back into the parametric line gives us the Cartesian points of the intersection. What about the complex roots? Well, the restriction on \(t\) is that it has to be a real number, so in the case of 2 complex roots, we say the line doesn't intersect the circle.

This is a simpler case than the line-circle intersection, although it involves a surface and a curve. A plane is algebraically a degree-1 polynomial in implicit form, so according to Bezout's theorem, they should intersect at exactly 1 point. We take the plane in implicit form and the line in parametric form and apply our method as above:

\[

\begin{aligned}

P(x,y) &= ax+by+cz+d=0 \\

L(x(t),y(t),z(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= x_0+ut \\ y&=y_0+vt \\ z &= z_0+wt \\ \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

We substitute the parametric equations into the implicit form and solve for \(t\) as before:

\[

\begin{aligned}

P(x(t),y(t),z(t)) = 0 &= a(x_0+ut)+b(y_0+vt)+c(z_0+wt)+d \\

&= (ax_0+by_0+cy_0+d) + (au+bv+cw)t \\

t &= -\frac{ax_0+by_0+cy_0+d}{au+bv+cw} \\

&= -\frac{(a,b,c,d)\cdot(x_0,y_0,z_0,1)}{(a,b,c,d)\cdot(u,v,w,0)}

\end{aligned}

\]

By substituting the value for \(t\) into the parametric line, we get the intersection point of the line and the plane.

Ray-Triangle Intersection

One method of ray-triangle intersection is basically a two-step process, the first step being computing the point on the plane that intersects the ray (line). The next is to determine if the point lies inside the triangle. Barycentric coordinates is a common method of doing this, but another method would be to create lines in the plane with directions such that a point inside the triangle would be on the same side of each line (i.e. the point would be on the left or right sides of each line). The side of the line can be computed using the scaled signed distance as detailed above.

Just to illustrate how general this method is, let's take a more advanced example:

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,y) &= x^2+y^2-1 = 0 \\

L(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= 2t-1 \\ y&=8t^2-9t+1 \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

The picture above shows the curves. The red curve is the parametric curve and the black curve is the implicit curve. As you can see, there are 4 real intersections, and since both curves are degree-2 we should end up with all real roots.

Inserting definitions of the parametric equations into the implicit form, we get:

\[

\begin{aligned}

f(x(t),y(t)) &= (2t-1)^2+(8t^2-9t+1)^2-1 \\

&= 64t^4-144t^3+101t^2-22t+1 \\

&= 0

\end{aligned}

\]

This is a quartic polynomial, so a more advanced numeric root finding method needs to be used, like bisection, regula falsi, or Newton's method. The roots of the polynomial are t = 0.06118, 0.28147, 0.90735, and 1.0. We do have all real roots, so Bezout's theorem is satisfied.

If the parametric curves are rational, then this method needs to be slightly modified. Rational parametric curves are usually of the form:

\[x = \frac{a(t)}{c(t)}, \, y = \frac{b(t)}{c(t)}\]

We can use homogeneous coordinates here really well. Since we have the mapping \((x,y) = (X/W,Y/W)\), we can define each homogeneous coordinate as \(X = a(t),\,Y = b(t),\,W=c(t)\). We also need to modify the implicit curve to handle homogeneous coordinates too, but this isn't very hard. Let's illustrate with an example:

\[

\begin{aligned}

S(x,y) &= x^2+2x+y^2+1 = 0 \\

P(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases}

x &= \frac{t^2+t}{t^2+1} \\

y &= \frac{2t}{t^2+1} \\

\end{cases}

\end{aligned}\]

Our parametric curve in homogeneous coordinates is \(X = t^2+t\),\(Y=2t\),and \(W={t^2+1}\). Our implicit curve can be changed to use homogeneous coordinates by substituting in the mapping \((x,y) = (X/W,Y/W)\):

\[

\begin{aligned}

S &= \left(\frac{X}{W}\right)^2+2\left(\frac{X}{W}\right)+\left(\frac{Y}{W}\right)^2+1 \\

&= X^2+2XW+Y^2+W^2 \\

\end{aligned}

\]

We can substitute our homogeneous coordinate equation into our modified implicit function:

\[

\begin{aligned}

S &= (t^2+t)^2 + 2(t^2+t)(t^2+1) + (2t)^2 + (t^2+1)^2 \\

&= 4t^4+6t^3+5t^2+4t+1 \\

&= 0 \\

\end{aligned}

\]

We get 2 real roots at t = 0.3576 and t = 1, and 2 complex roots. Both curves are degree-2, so Bezout's theorem is satisfied as well.

The way to solve intersections of 2 parametric curves is via implicitization of one of the curves. This can be a very fast method, but it suffers from numeric instability for high degree polynomials. We won't cover implicitization in this article, but there is a lot of literature on it out there.

A Bezier curve is just a degree-n Bernstein polynomial, which means it's just a regular polynomial of a different form. The above methods work well for Bezier curves, but they are more efficient and more numerically stable if modified slightly to take advantage of the Bernstein form. We won't cover this here, but there is literature out there on this as well.

These common methods of intersection testing can greatly aid any game programmer, whether purely for graphics or other game-specific logic. Hopefully you can make some use of these simple, yet powerful techniques.

A lot of the information here was taught to me by Dr. Thomas Sederberg (associate dean at Brigham Young University, inventor of the T-splines technology, and recipient of the 2006 ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics Achievement Award). The rest came from my own study of relevant literature. The article image is from his self-published book, Computer-Aided Geometric Design.

15 Jan 2014: Initial release

For this article, I'm assuming you know all about vectors, points, dot and cross products. We'll cover some quick properties of polynomials, some things about some basic curves, and then go over intersection tests.

Polynomials

The Stone-Weierstrass theorem states that any continuous function defined on a closed interval can be uniformly approximated as closely as desired with a polynomial function. For graphics and game development, that means that most 2D objects we deal with can be expressed as polynomials. The key to these intersection test methods is using that to our advantage.

Bezout's Theorem

In order to find all our intersection points, we need to know how many intersections there can be between 2 polynomials. Bezout's theorem states that for a planar algebraic curve of degree n and a second planar algebraic curve m, they intersect in exactly mn points if we properly count complex intersections, intersections at infinity, and possible multiple intersections. If they intersect in more than that number, then they intersect at infinitely many points, which means that they are the same curve.

Bezout's theorem also extends to surfaces. A surface of degree m intersects a surface of degree n in a curve of degree mn. As well, a space curve of degree m intersects a surface of degree n in mn points.

The key here is to identify how to count intersections. For example, if 2 curves are tangent, they intersect twice. If they have the same curvature, then they intersect 3 times. Simple intersections (not tangent and not self-intersecting) are counted once. So how do we count intersections at infinity? Using homogeneous coordinates, of course!

Homogeneous Coordinates

Counting intersections at infinity sounds hard, but we can use homogeneous coordinates to do this. Here, we define a point in 3D homogeneous space \((X,Y,W)\) to correspond to a 2D point \((x,y)\) whose coordinates are \((X/W,Y/W)\). This means a 3D homogeneous point \((4,2,2)\) corresponds to a the 2D point \((4/2,2/2) = (2,1)\). Going the other way, the 2D point \((3,1)\) becomes the 3D point \((3,1,1)\), since the transformation back to 2D is simply \((3/1,1/1) = (3,1)\). This creates some weird equalities, but you can visualize this 3D-2D transformation as projecting the points (and curves) in 3D onto the plane \(z=1\).

This helps us with define infinities with finite numbers. Let's say we have the point \((2,3,1)\) in homogeneous coordinates. If we changed the weight coordinate W so that we had \((2,3,0.5)\), the 2D point would be \((4,6)\). Smaller weights mean larger projected coordinates. As the weight approaches zero, the 2D point gets larger and larger, until at W = 0, the projected point is at infinity. Thus, any homogeneous point \((X,Y,0)\) is a point at infinity.

Aside: Equations in Homogeneous Form

Usually, polynomials have terms that differ in their algebraic degrees. Some are quadratic, some cubic, some constant, etc. The polynomial takes the following form:

\[f(x,y) = \sum_{i+j\le n} a_{ij}x^iy^j = 0 \]

However, the same curve can be expressed in homogeneous form by adding a homogenizing variable w:

\[f(X,Y,W) = \sum_{i+j+k = n} a_{ij}X^iY^jW^k = 0 \]

Here, every term in the polynomial is of degree n.

Equation Types

To use polynomials effectively, we need to be familiar with how they can be expressed. There are basically 3 types of equations that can be used to describe planar curves: parametric, implicit, and explicit. If you've only had high-school math, you've probably dealt with explicit curves a lot and not so much with the others.

Parametric: The curve is specified by a real number \(t\) and each coordinate is given by a function of \(t\), like \(x = x(t)\) and \(y = y(t)\). Rational polynomials are defined the same way, but each coordinate divided by a different function of \(t\), like \(x = x(t) / w(t)\) and \(y = y(t)/w(t)\).

Implicit: This curve takes the form \(f(x,y) = 0\), where the point \((x,y)\) is on the curve.

Explicit: This is really a special case of both parametric and implicit forms. The explicit form of a curve is the classic \(y=f(x)\) form.

Lines

Let's start with a very basic curve: the line. It's a degree-1 polynomial. There are many definitions of this kind of curve. Some are helpful for games and others...not so much. Some you may have seen in algebra class and others you may be seeing for the first time.

Common Forms

Slope-intercept: \( y = mx+b \)

Point-slope: \( y - y_0 = m(x-x_0) \)

Affine: \( P(t) = [(t_1-t)P_0+(t-t_0)P_1] / (t_1-t_0) \)

Vector Implicit: \((P-P_0)\cdot n = 0\)

Parametric: \( P(x(t),y(t)) = (x_0+at,y_0+bt) \)

Algebraic Implicit: \( ax+by+c=0 \)

In secondary schools, they use the first 2 methods almost exclusively, but these turn out to be the least helpful for computing. Here, I've tried to order the definitions from least helpful to most helpful for our needs.

Implicit Form, Line-Point, and Line-Line Intersection

Probably one of the most useful forms, the implicit form is nice for a few reasons. First, we can express it in homogeneous coordinates: \(aX+bY+cW=0\). From here, we can define the coordinates as an ordered triple \((a,b,c)\) and then modify the equation to use the dot product so we can use a simple test if a point lies on a given line in implicit form:

\[L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) = 0\]

Signed Distance From a Line

Although this isn't strictly an intersection test, this method is valuable enough to mention here. Although points that lie on a line satisfy the equation \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) = 0\), if the point is not on the line, the scalar value can let us know on which side of the line the point lies by the sign. If \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) > 0\), the point lies on one side of the line; if \(L(a,b,c) \cdot P(X,Y,W) < 0\) it lies on the other. This is a convenient way of dividing a plane into 2 separate regions.

This scalar value is also a scaled distance from the line. If only the relative position of a point from the closest point on a line is desired, then this scalar can suffice. However, if true distance is required, then the full signed distance formula for a point \((x,y)\) from an implicit line defined by the ordered triple \((a,b,c)\) is given by the following:

\[D = \frac{ax+by+c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}\]

Implicit Line from 2 Points

This ordered triple form a convenient way to define coordinate axes. For example, the x-axis can be defined as \((0,1,0)\) and the y-axis can be defined as \((1,0,0)\). The ordered triple is also really nice because we can compute it really easily if we have 2 points. Let's go back to our vector math to see how this might work.

In the above picture, two vectors \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are crossed to produce a 3rd vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a}\times\vec{b}\). This vector \(\vec{c}\) is orthogonal to the vectors \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\), meaning that \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). This is important for this next neat trick.

Imagine we have points \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). To tie back into the example above, let's let \(\vec{a} = P_1 = (x_1,y_1,w_1)\) and \(\vec{b} = P_2 = (x_2,y_2,w_2)\). If we cross these vectors, we get a vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a} \times\vec{b}\) for which \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). Since \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are points, we could say that \(\vec{c} = (a,b,c)\), an implicit ordered triple that passes through both points. We can check that the line given by \((a,b,c)\) passes through both points by the dot product method.

\[L(a,b,c) = P(X_1,Y_1,W_1) \times P(X_2,Y_2,W_2)\]

Line-Line Intersection

Using the same kind of logic, we can get the point at which 2 lines intersect. To use the cross product example again, let's let the vectors be the ordered triples of 2 implicit lines, \(\vec{a} = (a_1,b_1,c_1)\) and \(\vec{b} = (a_2,b_2,c_2)\). Again, crossing these vectors yields a vector \(\vec{c} = \vec{a} \times\vec{b}\) for which \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{a} = 0\) and \(\vec{c}\cdot\vec{b} = 0\). Since \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are lines, we could say that \(\vec{c} = (X,Y,W)\), the intersection point of both lines. This point has to be on both lines, and we can verify that using the dot-product method.

\[P(X,Y,W) = L(a_1,b_1,c_1) \times L(a_2,b_2,c_2)\]

Connection to Bezout's Theorem

Lines are degree-1 algebraic curves. Bezout's theorem states that 2 lines must intersect at exactly 1 point. So what happens with parallel lines? Well, if we use homogeneous coordinates, the intersection point will take the form \((X,Y,0)\), a point at infinity. Bezout's theorem still holds for that case.

Parametric-Implicit Curve Intersection

Sometimes it's advantageous to define some curves as parametric and some as implicit to solve for intersections. Most times, it's better to define the simpler curve as parametric and the more complex curve as implicit is possible. This method solves for all algebraic intersections, which may or may not be "real" intersections. As well, multiple roots might come up, in which case we have to reconcile this with our intersection counting methods above.

Line-Circle Intersection

Let's take a fairly common case: line-circle intersection. Bezout's theorem says we will get 2 intersections since a circle is a degree-2 algebraic curve. The parametric line at point \((x_0,y_0)\) with direction \((c,d)\) and implicit circle centered at \((a,b)\) with radius \(r\) are defined as follows:

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,y) &= (x-a)^2+(y-b)^2-r^2 = 0 \\

L(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= x_0+ct \\ y&=y_0+dt \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

We can substitute the parametric equations into the implicit equation to get a polynomial in terms of the parameter \(t\). The roots of the polynomial are the parameter values at which the line intersects the circle. Substituting, we get:

\[

\begin{aligned}

0 &= (x_0+ct-a)^2+(y_0+dt-b)^2-r^2 \\

&= [c^2t^2+2c(x_0-a)t+(x_0-a)^2]+[d^2t^2+2d(y_0-b)t+(y_0-b)^2]-r^2 \\

&= (c^2+d^2)t^2+2[c(x_0-a)+d(y_0-b)]t + [(x_0-a)^2+(y_0-b)^2-r^2] \\

&= At^2+Bt+C \\

\end{aligned}

\]

This looks promising. The quadratic formula can solve really quickly for the roots of the polynomial:

\[t=\frac{-B\pm\sqrt{B^2-4AC}}{2A}\]

The result of this will either be 2 complex roots, 1 real root, or 2 real roots, depending on the discriminant \(B^2-4AC\). The 1 real root case means the line is tangent to the circle, which according to our intersection counting rules above, we count twice. Bezout's theorem still holds. (Note: technically we have 1 real root with multiplicity 2 since we have the roots \(t = (-B+0)/2A\) and \(t = (-B-0)/2A\).)

That might be nice mathematically, but what does that mean for us? Well, the parameter \(t\) has to be a real number, so the real roots are values of \(t\) that the line intersects, so plugging the roots back into the parametric line gives us the Cartesian points of the intersection. What about the complex roots? Well, the restriction on \(t\) is that it has to be a real number, so in the case of 2 complex roots, we say the line doesn't intersect the circle.

Line-Plane Intersection

This is a simpler case than the line-circle intersection, although it involves a surface and a curve. A plane is algebraically a degree-1 polynomial in implicit form, so according to Bezout's theorem, they should intersect at exactly 1 point. We take the plane in implicit form and the line in parametric form and apply our method as above:

\[

\begin{aligned}

P(x,y) &= ax+by+cz+d=0 \\

L(x(t),y(t),z(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= x_0+ut \\ y&=y_0+vt \\ z &= z_0+wt \\ \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

We substitute the parametric equations into the implicit form and solve for \(t\) as before:

\[

\begin{aligned}

P(x(t),y(t),z(t)) = 0 &= a(x_0+ut)+b(y_0+vt)+c(z_0+wt)+d \\

&= (ax_0+by_0+cy_0+d) + (au+bv+cw)t \\

t &= -\frac{ax_0+by_0+cy_0+d}{au+bv+cw} \\

&= -\frac{(a,b,c,d)\cdot(x_0,y_0,z_0,1)}{(a,b,c,d)\cdot(u,v,w,0)}

\end{aligned}

\]

By substituting the value for \(t\) into the parametric line, we get the intersection point of the line and the plane.

Ray-Triangle Intersection

One method of ray-triangle intersection is basically a two-step process, the first step being computing the point on the plane that intersects the ray (line). The next is to determine if the point lies inside the triangle. Barycentric coordinates is a common method of doing this, but another method would be to create lines in the plane with directions such that a point inside the triangle would be on the same side of each line (i.e. the point would be on the left or right sides of each line). The side of the line can be computed using the scaled signed distance as detailed above.

Higher-Degree Curve Intersection

Just to illustrate how general this method is, let's take a more advanced example:

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,y) &= x^2+y^2-1 = 0 \\

L(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases} x &= 2t-1 \\ y&=8t^2-9t+1 \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

The picture above shows the curves. The red curve is the parametric curve and the black curve is the implicit curve. As you can see, there are 4 real intersections, and since both curves are degree-2 we should end up with all real roots.

Inserting definitions of the parametric equations into the implicit form, we get:

\[

\begin{aligned}

f(x(t),y(t)) &= (2t-1)^2+(8t^2-9t+1)^2-1 \\

&= 64t^4-144t^3+101t^2-22t+1 \\

&= 0

\end{aligned}

\]

This is a quartic polynomial, so a more advanced numeric root finding method needs to be used, like bisection, regula falsi, or Newton's method. The roots of the polynomial are t = 0.06118, 0.28147, 0.90735, and 1.0. We do have all real roots, so Bezout's theorem is satisfied.

Higher-Degree Rational Curve Intersection

If the parametric curves are rational, then this method needs to be slightly modified. Rational parametric curves are usually of the form:

\[x = \frac{a(t)}{c(t)}, \, y = \frac{b(t)}{c(t)}\]

We can use homogeneous coordinates here really well. Since we have the mapping \((x,y) = (X/W,Y/W)\), we can define each homogeneous coordinate as \(X = a(t),\,Y = b(t),\,W=c(t)\). We also need to modify the implicit curve to handle homogeneous coordinates too, but this isn't very hard. Let's illustrate with an example:

\[

\begin{aligned}

S(x,y) &= x^2+2x+y^2+1 = 0 \\

P(x(t),y(t)) &= \begin{cases}

x &= \frac{t^2+t}{t^2+1} \\

y &= \frac{2t}{t^2+1} \\

\end{cases}

\end{aligned}\]

Our parametric curve in homogeneous coordinates is \(X = t^2+t\),\(Y=2t\),and \(W={t^2+1}\). Our implicit curve can be changed to use homogeneous coordinates by substituting in the mapping \((x,y) = (X/W,Y/W)\):

\[

\begin{aligned}

S &= \left(\frac{X}{W}\right)^2+2\left(\frac{X}{W}\right)+\left(\frac{Y}{W}\right)^2+1 \\

&= X^2+2XW+Y^2+W^2 \\

\end{aligned}

\]

We can substitute our homogeneous coordinate equation into our modified implicit function:

\[

\begin{aligned}

S &= (t^2+t)^2 + 2(t^2+t)(t^2+1) + (2t)^2 + (t^2+1)^2 \\

&= 4t^4+6t^3+5t^2+4t+1 \\

&= 0 \\

\end{aligned}

\]

We get 2 real roots at t = 0.3576 and t = 1, and 2 complex roots. Both curves are degree-2, so Bezout's theorem is satisfied as well.

Parametric-Parametric Curve Intersection

The way to solve intersections of 2 parametric curves is via implicitization of one of the curves. This can be a very fast method, but it suffers from numeric instability for high degree polynomials. We won't cover implicitization in this article, but there is a lot of literature on it out there.

Bezier Curve Intersection

A Bezier curve is just a degree-n Bernstein polynomial, which means it's just a regular polynomial of a different form. The above methods work well for Bezier curves, but they are more efficient and more numerically stable if modified slightly to take advantage of the Bernstein form. We won't cover this here, but there is literature out there on this as well.

Conclusion

These common methods of intersection testing can greatly aid any game programmer, whether purely for graphics or other game-specific logic. Hopefully you can make some use of these simple, yet powerful techniques.

References

A lot of the information here was taught to me by Dr. Thomas Sederberg (associate dean at Brigham Young University, inventor of the T-splines technology, and recipient of the 2006 ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics Achievement Award). The rest came from my own study of relevant literature. The article image is from his self-published book, Computer-Aided Geometric Design.

Article Update Log

15 Jan 2014: Initial release