I have been writing an DirectX / OpenGL rendering engine recently. As you may know, DirectX is by default associated with a left-handed coordinate system (LH) and OpenGL with a right-handed system (RH). You can compare both of them in the article title image to the right. You can look at those two systems in another way. If you want to look in a positive direction, for LH, you have Y as UP axis and for RH, you have Z as UP axis. If you dont see it, rotate the RH system in the image. Today, in time of shaders and, you can use one or another in both systems, but you need to take care of few things.

I have calculated both versions of matrices for both systems. I am tired of remembering everything and/or calculating it all over again. For this reason I have created this document, where I summarize needed combinations and some tips & tricks. This is not meant to be a tutorial “How projection works” or “Where those values come from”. It is for people who are tired of looking how to convert one system to another or how to convert one API to another. Or it is for those who don't care “why” but they are happy to copy & paste of my equations (hovewer, don't blame me if there is something wrong).

RH system has become some kind of a standard in a computer graphics. However, for my personal purposes, LH system seems more logical to visualise. In my engine, I wanted to give the decision to the user. At the end, my system supports both orientations.

If we looked more closely at DirectX and OpenGL, we can see one important difference in a projection. It doesn't matter if we use LH or RH system, in DirectX projection is mapped to interval [0, 1] while in OpenGL to [-1, 1]. What does that mean? If we take the near clipping plane of a camera, it will be always mapped to 0 for DirectX, but in OpenGL it is more complicated. For LH system, near will be 1, but for RH, it will became -1 (see graphs 5 and 6 in a later section). Of course, we can use DirectX mapping in OpenGL (not the other way), but in that case, we are throwing away half of the depth buffer precision. In the following sections, we will discuss this more closely.

Personally, I think that whoever invented OpenGL depth coordinates must have had a twisted sense for humour. DirectX's solution is far better and easier to understand.

[Note]Matrix order used in this article will be row based. All operations will be done in order vector · matrix (as we can see at (1) ) with indexing from (2).</i>

![Attached Image: matrix_eq1.png]()

![Attached Image: matrix_eq2.png]()

For column based matrix, order of elements is reversed - matrix · vector . In a time of a fixed function pipeline, that was more problematic than today. In a time of shaders, we may use whatever system and layout we want and just change the order of operations or read values from the different positions in matrices.

In every transformation pipeline, we need to first transform geometry from the world coordinates to a view (camera) space. After that, you can do a projection transformation. View matrix must use the same system as your final projection, so it must be LR or RH. This section is mentioned only for complete look up, so you know how to transform a point. There will be no additional details for view transformation.

View matrix has the same layout for both of the systems (3)

![Attached Image: matrix_eq3.png]()

Differences are in base vectors and the last row elements calculation. You can see it in table 1.

Table 1: View vectors calculation. wLook is camera lookAt target, eye is camera position and wUp is camera up vector - usually [0,1,0]. "x" stands for a vector product

For “3D world” rendering, you will probably use a perspective projection. Most of the time (like in 90% of cases) you will need a simplified perspective matrix (with a symmetric viewing volume). Pattern for such a projection matrix can be seen at 4. As you can see, this matrix is symmetric. For column and row major matrices, this simplified pattern will be the same, but values of D and E will be transposed. Be aware of this, it can cause some headaches if you do it the other way and not notice it.

![Attached Image: matrix_eq4.png]() (4)

(4)

Now, how projection works. We have an input data in the view space coordinates. From those we need to map them into our screen. Since our screen is 2D (even if we have so called 3D display), we need to map a point to our screen. We take a simple example:

![Attached Image: matrix_eq5_6.png]()

where x,y,z,w is an input point ( w is a homogenous coordinate, if we want to “debug” on a paper, the best way is to choose this value as 1.0). Division by ( D · z ) is performed automatically after vertex shader stage.

From equations 5 we have coordinates of a point on 2D screen. You may see, that those values are not coordinates of pixel (like [756, 653]), but they are in a range [-1, 1] for both axis (in DirectX and also in OpenGL).

From equation 6 we have depth of pixel in range [0, 1] for DirectX and [-1, 1] for OpenGL. This value is used in depth buffer for closer / distant object recognition. Later on, we show how depth values look like.

Those +1 / -1 values, that you will obtain after projection, are known as a normalized device coordinates (NDC). They form a cube, where X and Y axis are in interval [-1, 1] for DirectX and OpenGL. Z axis is more tricky. For DirectX, you have an interval [0, 1] and for OpenGL [-1, 1] (see 2). As you can see now, NDC is a LH system, doesn't matter what input system you have chosen.

Everything, that is inside of this cube, is visible on our screen. Screen is taken as a cube face at Z = 0 (DirectX), Z = 1 (OpenGL LH) or Z = -1 (OpenGL RH). What you see on your screen is basically content of a NDC cube pressed to single plane.

We summarize computations for LH / RH system and for DirectX and OpenGL in two different tables. Those values are different for LH / RH system and of course for API used. In following sections, you can spot the differences. If you are interested where those values come from, look elsewhere (for example OpenGL matrices are explained here: Link). There are plenty of resources and it will be pointless to go over it again here.

DirectX

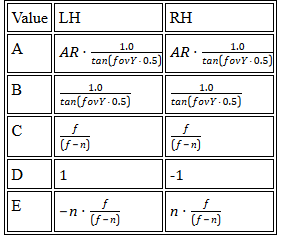

![Attached Image: table2.png]()

Table 2: Projection matrix calculation for DirectX. Input parametrs are: fovY - field of view in Y direction, AR - aspect ratio of screen, n - Z-value of near clipping plane, f - Z-value of far clipping plane

Changing only values at the projection matrix won't work as expected. If we render same scene with same DirectX device settings, we end up with turned scene geometry for one of those matrices. This is caused by depth comparison in depth buffer. To change this settings is a little longer in DirectX, than for OpenGL. You need to call functions in code snippet 1 with values in table 3.

Table 3: OpenGL setting for both systems

OpenGL

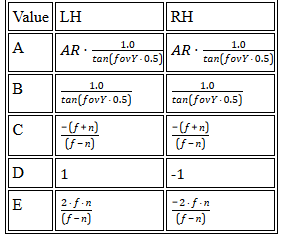

![Attached Image: table4.png]()

Table 4: Projection matrix calculation for OpenGL. Input parametrs are: fovY - field of view in Y direction, AR - aspect ratio of screen, n - Z-value of near clipping plane, f - Z-value of far clipping plane

Again, changing only values at the projection matrix won't work as expected. If we render same scene with same OpenGL device settings, we end up with turned scene geometry for one of those matrices. This is caused by depth comparison in depth buffer. We need to change two things as we see in table 5.

Table 5: OpenGL setting for both systems

Conclusion

If you set the comparison and depth buffer clear values incorrectly, most of the time, you will end up with result like on the figure 3. Correct scene should look like on the figure 4.

Using equation 6, we can calculate projected depth for any input value. If we do this for values in interval [near, far], we will get the following result (see image 5 and 6). Notice second graph x-axis. For RH system, we need to change sign of near to -near in order to obtain same results as for LH system. That means in plain language, that for LH we are looking in positive Z direction and for RH we are looking in negative Z direction. In both cases, viewer is located at origin.

From above graphs, we can see that for the distances near to the camera, there is a good precision in the depth buffer. On the other hand, for larger values the precision is limited. That is not always desired.

One possible solution is to keep your near and far distances together as close as possible. There will be less problems if you use interval [0.1, 10] instead of [0.1, 100]. This is not always possible if we want to render large 3D world enviroments. This issue can be however solved as we show in the next section.

As mentioned before, using a classic perspective projection brings us a limited depth precision. The bigger the distance from viewer, the lower precision we have. This problem is often noticable as flickering pixels in distance.

We can partially solve this by logarithmic depth. We decrease precision for near surroundings, but we have almost linear distribution throughout the depth range. One disadvantage is that logarithm is not working for negative input. Triangles, that are partially visible and have some points behind viewer (negative Z axis), won't be calculated correctly. Shader programs usually won't crash with negative logarithm, but the result is not defined. There are two possible solutions for this problem. You either tesselate your scene to have triangles so small, that the problem won't matter, or you can write your depth in a pixel shader.

Writing depth in a pixel shader brings disadvantage with turned off depth testing for geometry before rasterizing. There could be some performance impact, but you can limit it by doing this trick only for near geometry, that could be affected. That way, you will need a condition in your shader or use different shaders based on geometry distance from viewer.

If you use this modification, be aware of one thing: The depth from vertex shader has range [-1, 1], but gl_FragDepth has range [0, 1]. It's again something OpenGL only, since DirectX has depth in [0, 1] all the time.

For a more detailed explenation, you can read an excellent article at Outtera blog (Link). Equations in their solution are using RH system (they aimed primary for OpenGL). So once again, we show same equation in LH and RH system. Both version are at table 6. This time only for OpenGL, since in DirectX problem can be solved, as proposed in article, by swapping near and far.

Table 6:Calculation of new Z coordinate for depth using log. C is linearized component, default value is 1.0, far is camera far plane distance, gl_Position is output value from vertex shader (in perspective projection). You MUST remember to multiply gl_Position.z by gl_Position.w before returning it from shader.

If you have read the Outtera article and looked at my equations, you may notice that I used gl_Position.z in logarithm calculations. I don't know if it is a mistake by Outtera, but with W, I have nearly same results for RH system (as if I used Z), but LH is totally messed up. Plus, W is already linearized depth (distance of point from viewer). So first visible point has W = near and last one has W = far.

If we plot classic vs logarithm depth with equations from 6, we end up with the two following graphs. Red curve is same as in previous chapter, green one is our logarithmic depth.

You can observe the effect of both projections (classic and logarithmic one) at this video (rendered with LH projection in OpenGL):

Last section related to a projection will be a little different. So far, we have discussed perspective projection and precision for rendering. In this section, another important aspect will be converted to LH and RH system and to OpenGL / DirectX.

Oblique projection is not some kind of special projection, that makes everything shiny. It is classic perspective projection, only with improved clipping planes. Clipping plane for classic projection is near and far, but here we change near to get different effect. This kind of projection is mostly used for water reflection texture rendering. Of course, we can set clipping plane manually in OpenGL or in DirectX, but that won't work in a mobile version (OpenGL ES), a web version (WebGL) and in DirectX we will need a different set of shaders. Bottom line, solution with clipping plane is possible, but not as clean as oblique projection.

First we need to precompute some data. For a clipping, we need obviously a clipping plane. We need it in our current projective space coordinates. This can be achieved by transforming our plane vector with transposed inverse of the view matrix (we are assuming that the world matrix is set as identity).

Now calculate the clip-space corner point opposite the clipping plane

Transform q into camera space by multiplying it with the inverse of the projection matrix. For a simplified calculation, we have already used an inverted projection matrix.

DirectX

In DirectX system, we need to be careful, because original article is using OpenGL projection space with Z coordinate in range [-1, 1]. This is not possible in DirectX, so we need to change equations and recalculate them with Z in a range [0, 1].

Following solution is valid for LH system:

OpenGL

The following equations can be simplified, if we know handness of our system. Since we want to have an universal solution, I have used a full representation, that is independent on the used sytem.

In calculation of m3.Z we can use directly addition of value +1.0. If we write separate equations for LH and RH system, we can see why:

Final matrix composition

Final composition of the projection matrix is easy. Replace the third column with our calculated vector.

I have added an Excel file with projection matrices. You can experiment for yourself by changing near and far, or any other parameters and see the differences in depth. This is the same file that I used for creation of posted graphs.

I have calculated both versions of matrices for both systems. I am tired of remembering everything and/or calculating it all over again. For this reason I have created this document, where I summarize needed combinations and some tips & tricks. This is not meant to be a tutorial “How projection works” or “Where those values come from”. It is for people who are tired of looking how to convert one system to another or how to convert one API to another. Or it is for those who don't care “why” but they are happy to copy & paste of my equations (hovewer, don't blame me if there is something wrong).

RH system has become some kind of a standard in a computer graphics. However, for my personal purposes, LH system seems more logical to visualise. In my engine, I wanted to give the decision to the user. At the end, my system supports both orientations.

If we looked more closely at DirectX and OpenGL, we can see one important difference in a projection. It doesn't matter if we use LH or RH system, in DirectX projection is mapped to interval [0, 1] while in OpenGL to [-1, 1]. What does that mean? If we take the near clipping plane of a camera, it will be always mapped to 0 for DirectX, but in OpenGL it is more complicated. For LH system, near will be 1, but for RH, it will became -1 (see graphs 5 and 6 in a later section). Of course, we can use DirectX mapping in OpenGL (not the other way), but in that case, we are throwing away half of the depth buffer precision. In the following sections, we will discuss this more closely.

Personally, I think that whoever invented OpenGL depth coordinates must have had a twisted sense for humour. DirectX's solution is far better and easier to understand.

[Note]Matrix order used in this article will be row based. All operations will be done in order vector · matrix (as we can see at (1) ) with indexing from (2).</i>

For column based matrix, order of elements is reversed - matrix · vector . In a time of a fixed function pipeline, that was more problematic than today. In a time of shaders, we may use whatever system and layout we want and just change the order of operations or read values from the different positions in matrices.

World to View transformation

In every transformation pipeline, we need to first transform geometry from the world coordinates to a view (camera) space. After that, you can do a projection transformation. View matrix must use the same system as your final projection, so it must be LR or RH. This section is mentioned only for complete look up, so you know how to transform a point. There will be no additional details for view transformation.

View matrix has the same layout for both of the systems (3)

Differences are in base vectors and the last row elements calculation. You can see it in table 1.

| LH | RH | |

| look | |wLook - eye| | |eye - wLook| |

| right | |wUp x look| | |wUp x look| |

| up | |look x right| | |look x right| |

| A | -dot(right,eye) | dot(right,eye) |

| B | -dot(up, eye) | dot(up, eye) |

| C | -dot(look, eye) | dot(look, eye) |

Table 1: View vectors calculation. wLook is camera lookAt target, eye is camera position and wUp is camera up vector - usually [0,1,0]. "x" stands for a vector product

Perspective projection

For “3D world” rendering, you will probably use a perspective projection. Most of the time (like in 90% of cases) you will need a simplified perspective matrix (with a symmetric viewing volume). Pattern for such a projection matrix can be seen at 4. As you can see, this matrix is symmetric. For column and row major matrices, this simplified pattern will be the same, but values of D and E will be transposed. Be aware of this, it can cause some headaches if you do it the other way and not notice it.

(4)

(4)Now, how projection works. We have an input data in the view space coordinates. From those we need to map them into our screen. Since our screen is 2D (even if we have so called 3D display), we need to map a point to our screen. We take a simple example:

where x,y,z,w is an input point ( w is a homogenous coordinate, if we want to “debug” on a paper, the best way is to choose this value as 1.0). Division by ( D · z ) is performed automatically after vertex shader stage.

From equations 5 we have coordinates of a point on 2D screen. You may see, that those values are not coordinates of pixel (like [756, 653]), but they are in a range [-1, 1] for both axis (in DirectX and also in OpenGL).

From equation 6 we have depth of pixel in range [0, 1] for DirectX and [-1, 1] for OpenGL. This value is used in depth buffer for closer / distant object recognition. Later on, we show how depth values look like.

Those +1 / -1 values, that you will obtain after projection, are known as a normalized device coordinates (NDC). They form a cube, where X and Y axis are in interval [-1, 1] for DirectX and OpenGL. Z axis is more tricky. For DirectX, you have an interval [0, 1] and for OpenGL [-1, 1] (see 2). As you can see now, NDC is a LH system, doesn't matter what input system you have chosen.

Everything, that is inside of this cube, is visible on our screen. Screen is taken as a cube face at Z = 0 (DirectX), Z = 1 (OpenGL LH) or Z = -1 (OpenGL RH). What you see on your screen is basically content of a NDC cube pressed to single plane.

Figure 2: OpenGL (Left) and DirectX (Right) NDC

We summarize computations for LH / RH system and for DirectX and OpenGL in two different tables. Those values are different for LH / RH system and of course for API used. In following sections, you can spot the differences. If you are interested where those values come from, look elsewhere (for example OpenGL matrices are explained here: Link). There are plenty of resources and it will be pointless to go over it again here.

DirectX

Table 2: Projection matrix calculation for DirectX. Input parametrs are: fovY - field of view in Y direction, AR - aspect ratio of screen, n - Z-value of near clipping plane, f - Z-value of far clipping plane

Changing only values at the projection matrix won't work as expected. If we render same scene with same DirectX device settings, we end up with turned scene geometry for one of those matrices. This is caused by depth comparison in depth buffer. To change this settings is a little longer in DirectX, than for OpenGL. You need to call functions in code snippet 1 with values in table 3.

deviceContext->ClearDepthStencilView(depthStencilView, D3D11_CLEAR_DEPTH, 1.0f, 0); .... depthStencilDesc.DepthFunc = D3D11_COMPARISON_LESS_EQUAL; device->CreateDepthStencilState(&depthStencilDesc,&depthStencilState); deviceContext->OMSetDepthStencilState(depthStencilState, 1);Code 1: Code snippet settings for LH DirectX rendering

| LH | RH | |

| D3D11_CLEAR_DEPTH | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| depthStencilDesc.DepthFunc | D3D11_COMPARISON_LESS_EQUAL | D3D11_COMPARISON_GREATER_EQUAL |

Table 3: OpenGL setting for both systems

OpenGL

Table 4: Projection matrix calculation for OpenGL. Input parametrs are: fovY - field of view in Y direction, AR - aspect ratio of screen, n - Z-value of near clipping plane, f - Z-value of far clipping plane

Again, changing only values at the projection matrix won't work as expected. If we render same scene with same OpenGL device settings, we end up with turned scene geometry for one of those matrices. This is caused by depth comparison in depth buffer. We need to change two things as we see in table 5.

| LH | RH |

| glClearDepth(0) | glClearDepth(1) |

| glDepthFunc(GL_GEQUAL) | glDepthFunc(GL_LEQUAL) |

Table 5: OpenGL setting for both systems

Conclusion

If you set the comparison and depth buffer clear values incorrectly, most of the time, you will end up with result like on the figure 3. Correct scene should look like on the figure 4.

Figure 3: Incorrectly set depth function and clear for current projection

Figure 4: Correctly set depth function and clear for current projection

Using equation 6, we can calculate projected depth for any input value. If we do this for values in interval [near, far], we will get the following result (see image 5 and 6). Notice second graph x-axis. For RH system, we need to change sign of near to -near in order to obtain same results as for LH system. That means in plain language, that for LH we are looking in positive Z direction and for RH we are looking in negative Z direction. In both cases, viewer is located at origin.

Figure 5: Projected depth with DirectX and OpenGL LH matrices (values used for calculation: near = 0.1, far = 1.0)

Figure 6: Projected depth with DirectX and OpenGL RH matrices (values used for calculation: near = -0.1, far = -1.0)

From above graphs, we can see that for the distances near to the camera, there is a good precision in the depth buffer. On the other hand, for larger values the precision is limited. That is not always desired.

One possible solution is to keep your near and far distances together as close as possible. There will be less problems if you use interval [0.1, 10] instead of [0.1, 100]. This is not always possible if we want to render large 3D world enviroments. This issue can be however solved as we show in the next section.

Depth precision

As mentioned before, using a classic perspective projection brings us a limited depth precision. The bigger the distance from viewer, the lower precision we have. This problem is often noticable as flickering pixels in distance.

We can partially solve this by logarithmic depth. We decrease precision for near surroundings, but we have almost linear distribution throughout the depth range. One disadvantage is that logarithm is not working for negative input. Triangles, that are partially visible and have some points behind viewer (negative Z axis), won't be calculated correctly. Shader programs usually won't crash with negative logarithm, but the result is not defined. There are two possible solutions for this problem. You either tesselate your scene to have triangles so small, that the problem won't matter, or you can write your depth in a pixel shader.

Writing depth in a pixel shader brings disadvantage with turned off depth testing for geometry before rasterizing. There could be some performance impact, but you can limit it by doing this trick only for near geometry, that could be affected. That way, you will need a condition in your shader or use different shaders based on geometry distance from viewer.

If you use this modification, be aware of one thing: The depth from vertex shader has range [-1, 1], but gl_FragDepth has range [0, 1]. It's again something OpenGL only, since DirectX has depth in [0, 1] all the time.

For a more detailed explenation, you can read an excellent article at Outtera blog (Link). Equations in their solution are using RH system (they aimed primary for OpenGL). So once again, we show same equation in LH and RH system. Both version are at table 6. This time only for OpenGL, since in DirectX problem can be solved, as proposed in article, by swapping near and far.

| LH | gl_Position.z = (-2.0) * log((-gl_Position.z) * C + 1.0) / log(far * C + 1.0) + 1.0 |

| RH | gl_Position.z = (2.0) * log((gl_Position.z) * C + 1.0) / log(far * C + 1.0) - 1.0 |

Table 6:Calculation of new Z coordinate for depth using log. C is linearized component, default value is 1.0, far is camera far plane distance, gl_Position is output value from vertex shader (in perspective projection). You MUST remember to multiply gl_Position.z by gl_Position.w before returning it from shader.

If you have read the Outtera article and looked at my equations, you may notice that I used gl_Position.z in logarithm calculations. I don't know if it is a mistake by Outtera, but with W, I have nearly same results for RH system (as if I used Z), but LH is totally messed up. Plus, W is already linearized depth (distance of point from viewer). So first visible point has W = near and last one has W = far.

If we plot classic vs logarithm depth with equations from 6, we end up with the two following graphs. Red curve is same as in previous chapter, green one is our logarithmic depth.

Figure 7: Projected depth with classic perspective and with logarithmic one in LH (values used for calculation: near = 0.1, far = 1.0, C = 1.0)

Figure 8: Projected depth with classic perspective and with logarithmic one in RH (values used for calculation: near = 0.1, far = 1.0, C = 1.0)

You can observe the effect of both projections (classic and logarithmic one) at this video (rendered with LH projection in OpenGL):

Oblique projection

Last section related to a projection will be a little different. So far, we have discussed perspective projection and precision for rendering. In this section, another important aspect will be converted to LH and RH system and to OpenGL / DirectX.

Oblique projection is not some kind of special projection, that makes everything shiny. It is classic perspective projection, only with improved clipping planes. Clipping plane for classic projection is near and far, but here we change near to get different effect. This kind of projection is mostly used for water reflection texture rendering. Of course, we can set clipping plane manually in OpenGL or in DirectX, but that won't work in a mobile version (OpenGL ES), a web version (WebGL) and in DirectX we will need a different set of shaders. Bottom line, solution with clipping plane is possible, but not as clean as oblique projection.

First we need to precompute some data. For a clipping, we need obviously a clipping plane. We need it in our current projective space coordinates. This can be achieved by transforming our plane vector with transposed inverse of the view matrix (we are assuming that the world matrix is set as identity).

Matrix4x4 tmp = Matrix4x4::Invert(viewMatrix); tmp.Transpose(); Vector4 clipPlane = Vector4::Transform(clipPlane, tmp);

Now calculate the clip-space corner point opposite the clipping plane

float xSign = (clipPlane.X > 0) ? 1.0f : ((clipPlane.X < 0) ? -1.0f : 0.0f); float ySign = (clipPlane.Y > 0) ? 1.0f : ((clipPlane.Y < 0) ? -1.0f : 0.0f); Vector4 q = (xSign, ySign, 1, 1);

Transform q into camera space by multiplying it with the inverse of the projection matrix. For a simplified calculation, we have already used an inverted projection matrix.

DirectX

In DirectX system, we need to be careful, because original article is using OpenGL projection space with Z coordinate in range [-1, 1]. This is not possible in DirectX, so we need to change equations and recalculate them with Z in a range [0, 1].

Following solution is valid for LH system:

q.X = q.X / projection[0][0]; q.Y = q.Y / projection[1][1]; q.Z = 1.0f; q.W = (1.0f - projection[2][2]) / projection[3][2];

float a = q.Z / Vector4::Dot(clipPlane, q); Vector4 m3 = a * clipPlane;

OpenGL

The following equations can be simplified, if we know handness of our system. Since we want to have an universal solution, I have used a full representation, that is independent on the used sytem.

q.X = q.x / projection[0][0]; q.Y = q.Y / projection[1][1]; q.Z = 1.0 / projection[2][3]; q.W = (1.0 / projection[3][2]) - (projection[2][2] / (projection[2][3] * Matrix.M[3][2]));

float a = (2.0f * projection[2][3] * q.Z) / Vector4::Dot(clipPlane, q); Vector4 m3 = clipPlane * a; m3.Z = m3.Z + 1.0f;

In calculation of m3.Z we can use directly addition of value +1.0. If we write separate equations for LH and RH system, we can see why:

LH: m3.Z = m3.Z + projection[2][3]; //([2][3] = +1) RH: m3.Z = m3.Z - projection[2][3]; //([2][3] = -1)

Final matrix composition

Final composition of the projection matrix is easy. Replace the third column with our calculated vector.

Matrix4x4 res = projection; res[0][2] = m3.X; res[1][2] = m3.Y; res[2][2] = m3.Z; res[3][2] = m3.W;

Attachment

I have added an Excel file with projection matrices. You can experiment for yourself by changing near and far, or any other parameters and see the differences in depth. This is the same file that I used for creation of posted graphs.

References

- OpenGL Projection Matrix - http://www.songho.ca/opengl/gl_projectionmatrix.html

- Logarithmic Depth Buffer - http://outerra.blogspot.sk/2009/08/logarithmic-z-buffer.html

- http://www.terathon.com/gdc07_lengyel.pdf

- http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb205350%28v=VS.85%29.aspx

- http://www.codeproject.com/Articles/42848/A-New-Perspective-on-Viewing/

- Lengyel, Eric. “Oblique View Frustum Depth Projection and Clipping”. Journal of Game Development, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2005), Charles River Media, pp. 5–16. (http://www.terathon.com/code/oblique.html)